Kandinsky: composer of light

“The artist must train not only the eye but also his soul, so that it can weigh colours in its own scale and thus become a determinant in artistic creation.” — Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), born in Moscow, is widely considered a pioneer of abstract art and is often referred to as the father of abstraction. He played both piano and cello while growing up in Russia, and this early appreciation of music cultivated his sensitivity to tone, rhythm, and harmony from an early age — concepts that would later profoundly inform his visual theory.

At the age of thirty, Kandinsky made a radical life shift, moving to Munich in 1896 to study art. In doing so, he left behind a promising and secure career as an appointed lecturer (docent) in law and political economy. Around this time, a chance encounter with Claude Monet’s Haystacks proved transformative. Kandinsky later recalled that the painting’s lack of clear representation revealed to him that art did not need to depict the external world in order to carry emotional resonance. During this period, he began consciously exploring parallels between color and musical sound.

Between 1909 and 1910, Kandinsky attended performances of Arnold Schoenberg’s atonal compositions in Munich. Schoenberg, who was also a painter, had broken decisively with traditional harmonic rules. This radical freedom deeply affected Kandinsky and encouraged him to move further away from representational art.

The Letter

In January 1911, after attending another Schoenberg concert, Kandinsky wrote to the composer expressing his admiration. In the letter, Kandinsky praised Schoenberg for:

Breaking free from conventional harmony

Treating dissonance as expressive rather than something that needed resolution

Creating music guided by inner necessity rather than external rules

This concept of inner necessity would become central to Kandinsky’s own philosophy of art.

Just as Schoenberg abandoned a fixed home key, Kandinsky realized that a painting no longer required a central subject or representational anchor to be meaningful.

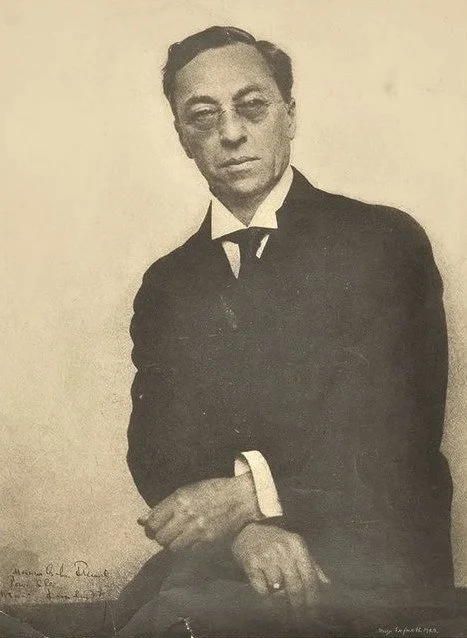

Kandinsky by Hugo Erfurth, 1923, Public domain. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1913, Kandinsky painted Composition VII (alongside earlier works he titled Improvisations), explicitly linking his paintings to musical structures. These titles reflected his belief that painting, like music, could communicate pure emotion without narrative or object. In 1911, Kandinsky published Concerning the Spiritual in Art, where he articulated a comprehensive system connecting musical and visual aesthetics:

Color = sound

Composition = symphony

Abstract form = pure expression

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII, 1913. Oil on canvas. Public domain. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This period marks Kandinsky’s full embrace of non-objective art, establishing him as one of the founders of abstraction. These pivotal events reveal a guiding principle behind Kandinsky’s work: art is not led by intellect alone, nor governed by external rules, but arises from an internal authority.

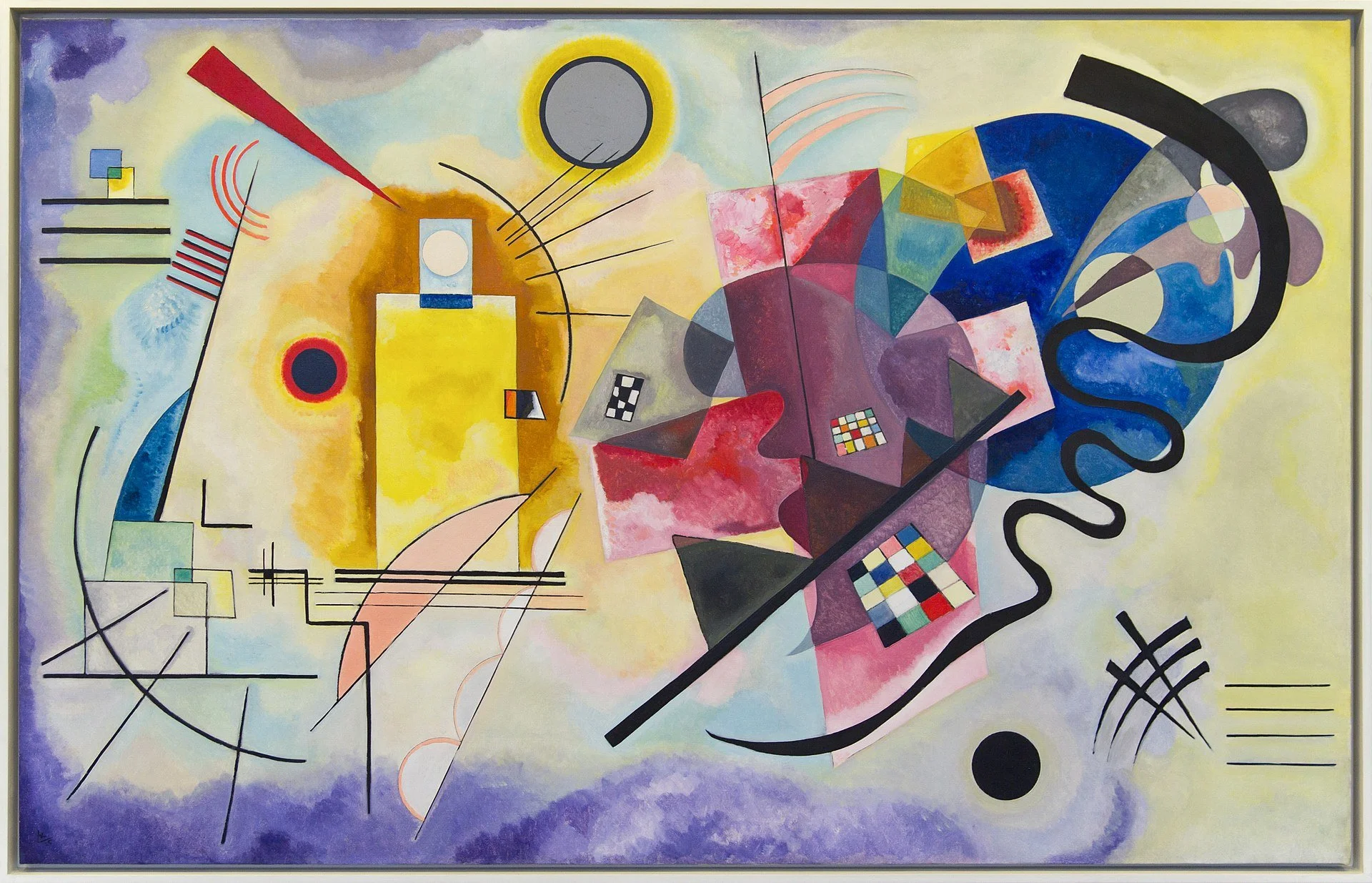

Felt truth weighs colours on its own scale.

Red is never just red.

Blue is never just blue.

Yellow‑Red‑Blue, every hue has a voice.

Through vibrant bursts and grounded shadows, Kandinsky’s palette reminds us that color is not decoration, it is feeling, movement, and intention. His work makes inner realities visible through inner necessity, translating states of consciousness into form, color, and rhythm.

Wassily Kandinsky, Yellow‑Red‑Blue (Jaune‑Rouge‑Bleu), 1925. Oil on canvas. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

Kandinsky emphasized contrast and harmony as tools for creating rhythm and movement, much like in musical composition. He saw colors as relational forces, where the interaction of color, shape, and negative space produces the “music” of the painting. These colors exude energy, dancing across the canvas and echoing frequencies much like notes arranged in a composed score.

By feeling into subtle inner movements, the artist moves between outer and inner worlds. Kandinsky believed that cultivating awareness, emotional literacy, silence, and depth — along with the ability to receive what lies beyond the visible — was essential to artistic creation. While proportion, color theory, composition, and observation are necessary, they represent only half of the creative truth available to the artist.

“Technique teaches you how to paint. The soul teaches you why and what must appear. Color, when truly sensed, evokes states of consciousness, moods, and inner movement.”

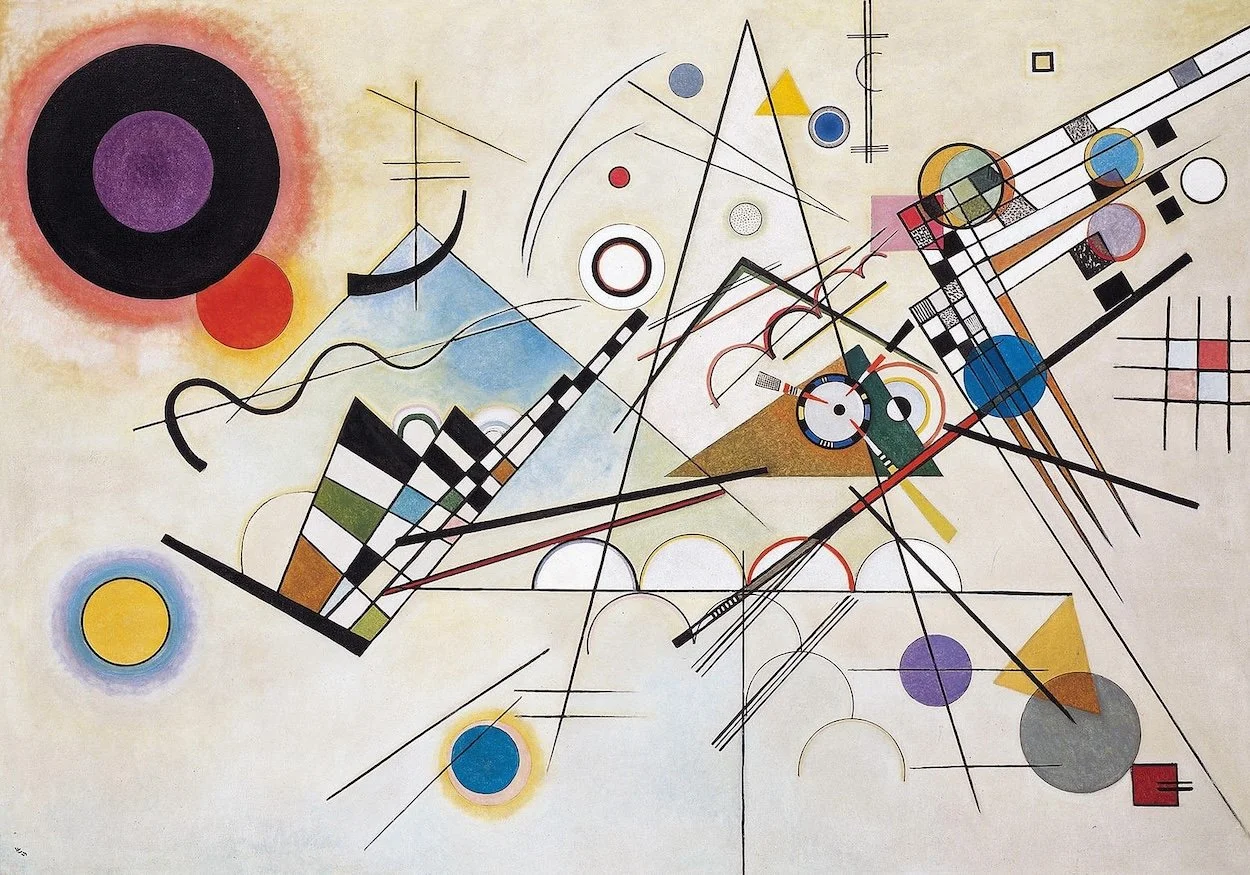

Composition VIII

Every shape evokes color, emotion, rhythm, and energy, contributing to a cohesive and dynamic dance.

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VIII, 1923. Oil on canvas. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

As the artist enters the incubatory space of creative receiving, Kandinsky believed they become a conduit for something much larger — creating not as performance, but as alignment, much like listening deeply to music.

Kandinsky’s approach continues to inspire our own studio practices: inviting a controlled dialogue between intuition and structure, guided by inner necessity. By allowing improvisation to loosen the intellectual grip and embracing the accident, we then refine the work through felt sense, harmony, and cohesive expression.

That aha moment, the moment of resonant transference, is where the viewer feels it too.